Exciting news: Emerging Pardalotes

Posted on 19 December, 2023 by Ivan

We are blessed to have some of the most wonderful volunteers and supporters we could ever hope for, who help keep our restoration and monitoring programs ticking along across the central Victorian region. We love to celebrate and engage with our dedicated volunteers and were excited to receive a nice story and photos from one such volunteer, Lou Citroën. Lou is a keen bird watcher, citizen scientist and photographer, and has been observing a family of Spotted Pardalote birds in his backyard in Castlemaine. These birds have the unusual habit of nesting in burrows, and Lou was lucky enough to have them do this next to his veggie patch in spring.

Please find Lou’s observations and photos below, of a very sweet take of the young Pardalotes leaving the nest for the first time. Great capture Lou, keep up the great work and passion!

Emerging Pardalotes, by Lou Citroën

I have some exciting news.

I was over the moon to have actually witnessed (AND photographed) the two young pardalotes emerging and leaving their burrow (with some encouragement from Mum and Dad) this morning (after about 7 weeks of incubation and feeding)!

Thinking that I would not stand a chance to be able to capture this special moment in time, I was very lucky to do so and share it with you with the photos.

For further information about Spotted Pardalotes, courtesy of Birdlife Australia, please click here.

If you’re interested in volunteer opportunities with Connecting Country please send a brief email to anna@connectingcountry.org.au detailing your relevant experience and availability.

Connecting Country (Mount Alexander Region) Inc is an incorporated, not-for-profit community organisation restoring landscapes across the Mount Alexander region. Donations help us continue this vital work. If you are in a position to contribute, please click here for more information on how to donate.

Large old tree profile: Chewton’s treasured long-leaved box

Posted on 14 December, 2023 by Ivan

Over the past 12 months, Connecting Country has been asking the local community to map our precious large old trees, through our new online mapping portal. The mapping portal aims to engage with the community about the importance of the old, and often large trees of central Victoria, as part of Connecting Country’s larger project, ‘Regenerate before it’s too late’.

Anyone can access the mapping portal. The community, including landholders, Landcarers and land managers, have been vital in mapping their favourite old trees across our region so far. To date, we have mapped over 30 old trees on the database and are keen for the community to continue mapping trees that are important to them and our local wildlife.

We will be highlighting some of the extraordinary trees that have been mapped, starting with a great entry from Joel B in Chewton, who uploaded a wonderful Long-leafed Box (Eucalyptus goniocalyx) in the Post Office Hill reserve, Chewton. We asked Joel to tell us what he loved about the tree and what made it a significant tree to him and his family. Thanks Joel! Please enjoy his words and images below, and scroll further for instructions on how to map a large, old tree yourself.

The coppiced long-leaved box of Chewton

…One of my favourite trees to visit is a coppiced long-leaved box on Post Office Hill reserve, Chewton. Its story is literally etched on it – first lopped, it has regrown with multiple branches, having survived a wildfire, multiple axe wounds and sawn-off branches, this is a living example of bush resilience!

In an area of limited natural tree hollows, one large branch has a hollow that has supported generations of brush-tailed phascogales in the decade I’ve been visiting it, with continual evidence of scats and scratchings on the branches and scats falling out of the hollow onto the forest floor below.

I imagine it has been a favourite roost or hunting perch for owls, judging by the pellets found below. In the day time it supports a range of our local woodland birds, from thornbills and honeyeaters in the canopy going after lerps, seasonal flowering and insects, to the larger ravens and currawongs that can be seen perching or tearing off bark on the larger branches looking for a tasty meal.

I always look forward to visiting and like to notice any activity…

Joel B

We need your help!

The mapping portal is now open for any community member to record the old trees in your area. You will need to register with the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) (its quick, easy and free), then upload a photo and enter the field details needed for the survey. The portal will ask you simple questions about the tree location, size, species, age (if known), health status and habitat value.

Trees can be tricky to identify, especially eucalypts. If you are unsure about the identification of the tree species, you can:

- Use the to iNaturalist app assist with identification – click here

- Refer to a good guidebook, like those published by Friends of the Box-Ironbark Forests – click here

- Visit the Castlemaine Flora website – click here

To record your large old tree, or view the field survey questions and required measurements – click here

The mapping portal uses BioCollect, an advanced but simple-to-use data collection tool developed by the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) and its collaborators. BioCollect helps users collect field biodiversity data for their own projects, while allowing the data to be easily copied into the ALA, where it can be publicly available for others to use in research, policy and management. This allows individual projects to collectively contribute to ‘big science’.

By recording these trees, you will help build our understanding of the large old trees in our region, and contribute to the largest biodiversity database in our country. As the database grows, you can also access the portal to learn about other wonderful large old trees in our area and view the photos.

We are most grateful for our generous project support from the Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation. The foundation aims ‘To encourage and support organisations that are capable of responding to social and ecological opportunities and challenges.’ To learn more about Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation – click here

Give the gift of hope for woodland birds this Christmas

Posted on 11 December, 2023 by Ivan

It’s never been more important to act on landscape restoration and provide critical habitat for our woodland birds of central Victoria. This Christmas, give the gift of hope to our threatened woodland bird population.

With every gift, you are helping Connecting Country to plant vital habitat and restore our degraded woodlands. As well as removing carbon from the atmosphere, these woodlands create habitat and ecosystems for our most treasured birds and other endangered wildlife. Do more than wish for change this Christmas. Take action to continue this important work today and restore our landscapes for your loved ones and future generations.

Today we are launching our ‘Christmas Gift for Woodland Birds’ campaign and asking our community to give the gift of habitat for our local wildlife this Christmas.

$20 plants 2 habitat and food plant to support woodland birds

$50 plants 5 habitat and food plants to support woodland birds

$150 purchases and installs a nest box for wildlife

$500 supports the establishment of a habitat corridor

$1000 can support landscape-scale carbon sinks and habitat corridors

Click here to make a gift contribution this Christmas

The Diamond Firetail is a small threatened bright finch with a black band of white diamond spots. Photo Geoff Park

Thank you for supporting our shared vision for landscape restoration across the Mount Alexander region of central Victoria. You can be assured that any financial support from you will be well spent, with 100% invested into our core work of supporting and implementing landscape restoration in our local area. We run a lean operation and our small team of part-time staff attracts voluntary support that ensures every dollar goes a long way.

Over the past ten years, we have:

- Restored 13,000 ha of habitat across the Mount Alexander region, which equates to around 7.5% of the shire.

- Delivered more than 225 successful community education events.

- Installed more than 450 nestboxes for the threatened Brush-tailed Phascogale

- Maintained a network of 50 long-term bird monitoring sites

- Secured funding to deliver more than 60 landscape restoration projects.

- Supported an incredible network of over 30 Landcare and Friends groups.

Connecting Country has a long-established track record of revegetation success. Photo: Connecting Country

We should all be proud of what we’ve achieved. However, there’s much more to do.

Click here to make a gift contribution this Christmas

The Hidden Life of Skinks with Dr. Anna Senior

Posted on 16 October, 2023 by Hadley Cole

Our friends at Newstead Landcare are holding their Annual General Meeting this coming Tuesday 17 October 2023 and to celebrate will host special guest Dr. Anna Senior who will present on The Hidden Life of Skinks.

So many small things make our world tick, all interacting and keeping ecology in balance. Often hidden under a rock or small plant, or darting between cover, skinks play a pivotal role in our natural systems, but we rarely get a glimpse into their lives. Local ecologist Dr. Anna Senior will present on the fascinating world of skinks with a special focus on two threatened species that were the subject of her thesis. One of these, the Mountain Skink was recently discovered in the Wombat Forest.

When: Tuesday 17 October, 7.30pm

Where: Newstead Community Centre, 9 Lyons Street, Newstead VIC

All are welcome to attend and gold coin donations are appreciated. No bookings required.

Aussie Bird Count week 16-22 October 2023

Posted on 12 October, 2023 by Anna

Aussie Bird Count is Australia’s largest citizen science Project and is run by Birdlife Australia. Celebrate Bird Week 2023 and the tenth year of the Birdlife Australia’s Aussie Bird Count, by taking part!

The 2023 event will run from October 16 to 22. You can undertake as many bird counts as you like over this week long period. You can do this from your backyard, local park, or other favourite outdoor area.

To complete a count, all you need to do is spend 20 minutes in one spot, noting down the birds that you see. Binoculars will come in handy! If you can identify birds by their calls, please include these in your count, but if you aren’t sure of a bird without seeing it, please exclude it rather than making a guess. The Aussie Bird Count app has a handy field-guide to help you identify birds or you can visit the website (aussiebirdcount.org.au).

Once you have completed your count, you can submit it to Birdlife in two different ways:

Through the online web form (this form won’t be made live until the 10 October 2023)

OR

Via the free Aussie Bird Count phone app.

Last year 77,419 volunteers recorded a whopping 3.9 million birds of 620 different species! The vast amount of data collected during the bird count is invaluable for ecologists to track large-scale biodiversity trends. It is a wonderful way to get to know your local birds and connect with nature.

Register today and help make the tenth Aussie Bird Count the biggest and best yet.

For more information and to register, head to aussiebirdcount.org.au

If you’re lucky you might even come across some of the below birds. Can you identify each of these beauties?

Photos by Geoff Park and Damian Kelly.

Unveiling the Feathered Five’s Fading Symphony

Posted on 3 October, 2023 by Ivan

Three of our region’s Feathered Five are now listed as threatened. We have partnered with Birdlife Castlemaine District to deliver a series of blog posts describing these species, why they are threatened, and what we can do to support the conservation of these species into the future.

Extinction is a modern issue

The word extinction may evoke thoughts of the Wooly Mammoth or the Dodo. But in Australia, extinction is very much a contemporary issue. Currently 39 Australian mammal, and 22 bird species, are extinct; a further 154 birds are threatened with extinction. There are very recent, examples of extinctions. The Christmas Island Pipistrelle, a native bat, was last recorded in 2009 and formally declared extinct in 2019. Australia has also recently experienced its first documented reptile extinction. The Christmas Island Forest Skink went from being abundant and common up until the late 1990s to officially declared extinct in 2017. The last one died in captivity in 2014 less than five months after Australian legislation finally listed the species as endangered. Climate change represents a real and serious threat; the Bramble Cay Melomys, a bright-eyed native rodent, was declared extinct in 2014, likely due to rising sea levels impacting its island habitat. To date, there have been 100 extinctions in Australia since European colonisation (click here).

Our Famous (Feathered) Five… but for how long?

Just a few months ago, three of our beloved Feathered Five: the Diamond Firetail, the Hooded Robin (south-eastern), and the Brown Treecreeper (south-eastern), were listed under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. This means that the birds are now protected under federal legislation, but the declines that lead to these listings raises concerns about the status of these species into the long term.

What can you do? Conservation action in the Mount Alexander area

When a species is listed as threatened under the EPBC Act, the Australian Government develops a conservation advice document. These are intended to guide recovery planning and identify actions required for conservation and recovery of the species. For detailed information, you can read the conservation advice on the Diamond Firetail (click here), Brown Treecreeper (click here), and Hooded Robin (click here).

We would be devastated if our beloved Feathered Five slipped away and are hopeful that the listing of these species prompts wider conservation action. The listing of these species has prompted our friends and project partners, Birdlife Castlemaine District, to hold a meeting and consider what local actions could be undertaken to preserve these species. Into the future, we will be working with Birdlife Castlemaine District to seek funding support for these species, and to continue to raise the profile of these important species and do our best to conserve them.

Birdlife Castlemaine District have proposed the following simple, practical actions that landholders can take to help protect these special birds:

- Plant and retain locally indigenous shrubs and native grasses, and – importantly – allow them to go to seed, to provide food for seed-eating birds. Many gardens in the area already have wallaby grass – rather than mowing them, let them go to seed. Indigenous seeds are available from the Castlemaine Seed Library for a select number of species.

- Insects are also an important food source for some of the Feathered Five species, so plant local, insect-attracting plants. Reduce spraying of garden pests such as aphids.

- Provide water for birds and consider using water sources that hang to reduce predation from cats at bird baths.

Keep cats inside – see the Safe Cat website for information on how to keep cats (and wildlife) safe.

‘The urban garden in Box-Ironbark country’: FOBIF AGM 9 October 2023

Posted on 2 October, 2023 by Ivan

Our friends and project partners at Friends of the Box-Ironbark Forests (FOBIF) are having their AGM next Monday (9th October), featuring a talk by Dr Cassia Read on creating wildlife habitats in your garden. It is sure to be a great event and an important topic as we learn to co-exist with wildlife and create climate refuges around our homes and in our urban fringes. Please find the details below, provided by FOBIF.

FOBIF AGM: 9 October 2023

Our guest speaker at this year’s FOBIF Annual General Meeting will be Dr Cassia Read. Cassia is an ecologist, educator and garden designer, working at the intersection of biodiversity conservation and human wellbeing. She is Principal Ecologist and Co-Founder of the Castlemaine Institute and a FOBIF Committee member. She will be speaking on creating garden wildlife habitats.

The urban garden in Box-Ironbark country: Can you have your roses and fairywrens too?

Whatever your gardening style you can nudge your garden in a wildlife friendly direction. By adding habitat elements and designing for alignment between your needs and the needs of wildlife, you can create a stunning landscape that supports the remarkable creatures of Box Ironbark Country. Whether you prefer formal or wild gardens, cottage gardens or bush-blocks, by realising the potential of your garden oases you can be part of creating neighbourhood networks that will support people and biodiversity in a changing climate. This talk will provide you with know-how and inspiration about creating wildlife habitat, whether you’re starting from scratch or adding to an existing garden.

There will be a short formal AGM at 7.30 followed by Cassia’s talk. Supper will be provided and everyone is welcome. If you wish to nominate for the FOBIF committee, contact Bernard Slattery 0499 624 160. The meeting will be held in the Ray Bradfield Room, Victory Park, Castlemaine, with access from the IGA carpark or Mostyn Street.

Cassia in her Castlemaine garden.

Farewell Jess Lawton: thanks for all the birds

Posted on 2 October, 2023 by Ivan

We recently said ‘goodbye’ to our much-loved Monitoring Coordinator, colleague and friend, Jess Lawton. Jess has been an incredible asset to Connecting Country over the past (nearly) four years. She has provided inspiration and dedication to the role and will be missed by the community, landowners and citizen scientists with whom she managed and shared her passion, vision and wisdom. Her commitment to the monitoring program was a juggling act, with Jess managing the bird monitoring program and also the nestbox program. Jess’s efforts have made a huge difference to the local landscape, citizen scientists and the broader community.

We wish Jess all the very best in her new role at the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Federal Government) and are thrilled she will stay involved as a Connecting Country volunteer and supporter. Thanks also to all the landowners and volunteers who have supported Jess during this time. She will also give a talk at our upcoming AGM on her favourite topic, her deep love for the Brush-tailed phascogale. Stay tuned!

As one-star bird moves to another landscape, another arrives. We have been very fortunate to recruit a new Monitoring Coordinator – another local talent – Anna Senior. We welcome Anna with open arms and her talents from far and wide.

Local resident Anna Senior joins Connecting Country with a wealth of knowledge in monitoring and ecology. Photo: Connecting Country

Introducing Anna

Anna is a terrestrial ecologist with experience working in environmental management for state government and private sectors throughout eastern Australia. She has a passion for the conservation of lesser-known species, particularly reptiles. Her PhD explored the conservation biology and ecology of some of Victoria’s rarest lizards; the Guthega skink, mountain skink and swamp skink.

Anna lives in Castlemaine with her partner and enjoys tending her garden and looking after her ever-growing menagerie. Anna is based at Connecting Country on Mondays to Thursdays.

Anna has been supporting various projects at Connecting Country over the past eighteen months and is the perfect fit for the role of Monitoring Coordinator.

We are super-excited to have Anna on board, please say hello to Anna via her email or touch base if you would like to volunteer for our monitoring program: anna@connectingcountry.org.au

Mapping large old trees: let’s celebrate and protect these beauties!

Posted on 28 September, 2023 by Ivan

It has been a little over a year since we announced the arrival of our new mapping portal, aimed at helping community citizen scientists map the old, and often large, trees of Central Victoria.

We have been excited to see the database entries feed in over the past 12 months and we have now reached 25 large old trees entered into the portal. The majority of the entries have been around the Maldon, Welshmans Reef, Chewton, Castlemaine and Guildford areas, with a variety of citizen scientists taking some excellent photos and providing data about the tree species, age, height and habitat values. A special mention must go to Bev Phillips from Maldon Urban Landcare Group (MULGA), who entered a whopping 15 trees into the database. Well done, and a massive thank you, Bev, for your persistence and love for our landscape.

We thought it would be timely to publish the photos entered into the mapping portal so far, to highlight the diverse range of large old trees across our landscape. Interestingly, all of the 25 entries are Eucalyptus species, which are usually the tallest trees in the local landscape. We would love to see some other species mapped and entered, such as the Casuarinas, Acacias, Banksias, Bursarias and other local midstory species.

Please enjoy the images below, captured by our keen citizen scientists over the past 12 months.

The interactive mapping portal is part of Connecting Country’s larger project, ‘Regenerate before it’s too late‘ , engaging the community in the importance of old trees and how to protect them. Over the next two years (2024-2025), we will continue to host community workshops and develop engagement resources. We will also help local landholders with practical on-ground actions to protect their large old trees and ensure the next generation of large old trees across the landscape.

How to map and enter old trees in our mapping portal

We are asking the community, including landholders, Landcarers and land managers, to map their favourite old trees across our region. Anyone can access Connecting Country’s new online mapping portal. The portal uses BioCollect, an advanced but simple-to-use data collection tool developed by the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) and its collaborators. BioCollect helps users collect field biodiversity data for their own projects, while allowing the data to be easily copied into the ALA, where it can be publicly available for others to use in research, policy and management. This allows individual projects to collectively contribute to science across Australia.

The mapping portal is now open for any community member to record the old trees in your area. You will need to register with the Atlas of Living Australia (its easy and free), then upload a photo and enter the field details needed for the survey. The portal will ask you simple questions about the tree location, size, species, age (if known), health status and habitat value.

To record your large old tree, or view the field survey questions and required measurements – click here

By recording large old trees, you will help build our understanding of the large old trees in our region and contribute to the largest biodiversity database in our country. As the database grows, you can also access the portal to learn about other wonderful large old trees in our area and view the photos.

We are most grateful to the generous project support from the Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation. The foundation aims ‘To encourage and support organisations that are capable of responding to social and ecological opportunities and challenges.’ To learn more about Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation – click here

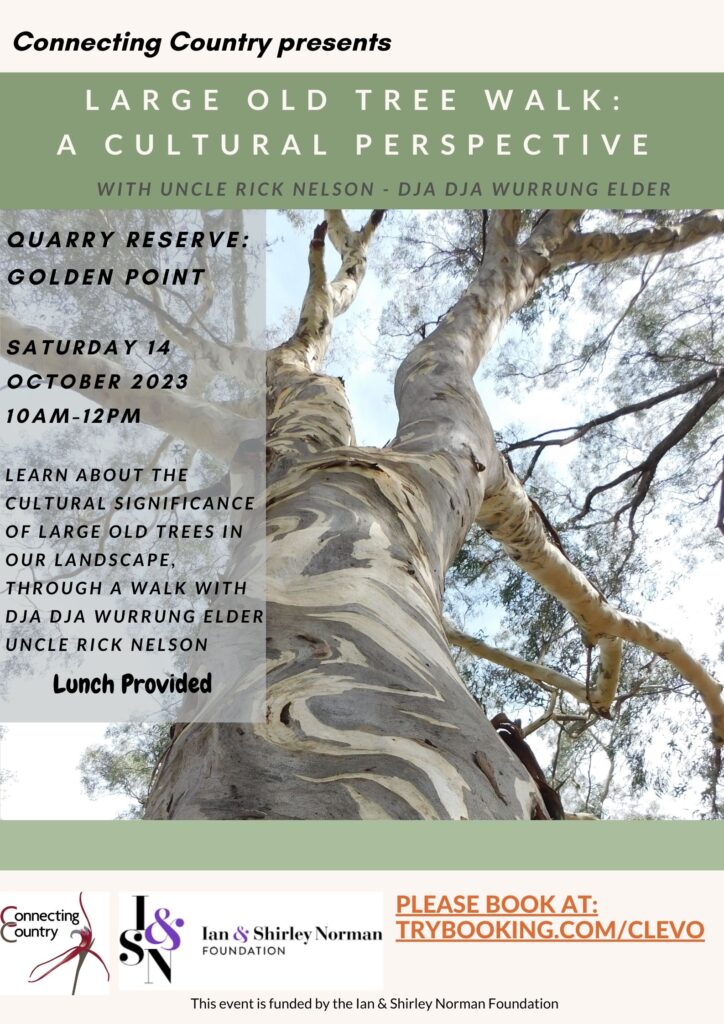

Large old tree walk: with Uncle Rick Nelson

Posted on 13 September, 2023 by Ivan

Connecting Country is thrilled to announce we are teaming up with Nalderun Education Aboriginal Corporation to deliver a cultural walk through the majestic large old trees at Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park in Golden Point, VIC. Come along and learn about these centuries-old trees, their cultural importance to the Dja Dja Wurrung people and the important role they play for biodiversity.

Our very special guest speaker is Dja Dja Wurrung Elder, Uncle Rick Nelson. He is a cultural advisor for the community on various matters for the Dja Dja Wurrung. Uncle Rick will take us on a guided walk, showing us some of the large old trees that sit quietly in our landscape and sharing their cultural significance. We are super excited to have his knowledge for this experience.

This is a free event for limited numbers, with lunch provided, so please book early to avoid disappointment.

For catering and logistical purposes, please register your attendance – click here

- When: Saturday 14 October 2023 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM

- Where: Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park, Golden Point 3451 (exact location will be revealed once you book)

The cultural walk is part of Connecting Country’s larger project, ‘Regenerate before it’s too late‘ aimed at engaging with the community about the importance of old trees and how to protect them. Over the next two years, we will develop engagement resources such as the old tree mapping portal, community events and an educational video. We will also help local landholders with practical on-ground actions to protect their large old trees and ensure the next generation of large old trees across the landscape.

- Click here to book, tickets are limited, so get in quick.

We are most grateful for our generous project support from the Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation. The foundation aims ‘To encourage and support organisations that are capable of responding to social and ecological opportunities and challenges.’ To learn more about Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation – click here

Learn more about Nalderun: Click here

Caring for old paddock trees: best practice

Posted on 11 September, 2023 by Ivan

Why protect paddock trees?

Paddock trees are often the oldest and most valuable habitat elements in agricultural landscapes. When paddock trees are cleared, it takes generations to replace the habitat they provided, including the insects and abundant nectar for birds and mammals, thick bark with cracks and crevices for microbats and small reptiles, and hollows for many significant species.

Paddock trees provide great habitat for travelling birds and wildlife between larger tracts of habitat. Photo: CC

Even standing dead trees, fallen branches and leaf litter offer valuable resources and should be retained wherever possible. Many paddock trees across our region are suffering die-back caused by old age, pests and disease, nutrient loading, soil compaction and lack of protection from intensive agricultural practices. These valuable giants are disappearing from our farming landscapes, often with no younger trees to replace them. However, we can take action to protect paddock trees to extend their life, and establish future generations.

How do we protect paddock trees?

- Fence off paddock trees from stock and machinery where possible, including space around them to promote natural regeneration.

- Incorporate existing paddock trees into revegetation plantings to improve the health of paddock trees and habitat value of revegetation.

- Leave dead paddock trees standing if possible – they contain cracks, crevices and hollows for wildlife such as microbats, and perching sites for birds of prey, parrots and water birds.

- Install stock-proof guards around young trees within paddocks if fencing is not feasible.

- Reduce grazing pressure: When native vegetation is browsed heavily, plants struggle to flower or set seed, and they have less habitat value. Grazing pressure also creates soil compaction and increased nutrient loads from manure.

A magnificent large Yellow Box (Eucalyptus melliodora) with young, successional trees growing in a fenced off area. Photo: CC

The importance of remnant vegetation

As most of our region was cleared for mining, timber and agriculture, any remaining native vegetation is extremely valuable for wildlife habitat and provides many on-farm benefits. Remnant vegetation is essentially indigenous plants growing in their natural environment. Protecting bush with lots of plant species and a complex structure is the highest priority. However, even a single large old tree, or a patch of native grasses or shrubs is worth protecting.

Revegetation is a valuable tool to increase species diversity, and expand or reconnect existing patches of bush to provide habitat for wildlife. However, the process of reestablishing high quality habitat in cleared areas is very labour-intensive and slow.

Large trees can take hundreds of years to grow and develop the tree hollows and create the fallen timber essential for many local wildlife species. Leaf litter can take decades to rebuild. Soil conditions in disturbed areas often favour weedy grass growth or inhibit growth of native plants, and some plant species are difficult to source or are unavailable.

Protecting what native vegetation is already there, and providing the conditions for it to regenerate naturally, is much cheaper and easier than re-establishing it from scratch. Eucalypts and other plants often self-seed, and if protected from grazing animals and weed competition, can start to establish. It is far easier to protect areas of seedlings with plant guards or fencing than investing in the planning, site preparation, planting, and ongoing maintenance of revegetation.

And finally……leave rocks, logs, branches and leaf litter

Leave logs on the ground to provide important resources for fungi, insects, reptiles, frogs, birds and small mammals. Clearing up rocks, logs, branches and leaves will exclude many woodland animals by removing the habitat elements they depend on. It will create a simple habitat and favour animals that are already common in our towns and farms, like magpies, cockatoos, rabbits, foxes and hares.

The gorgeous Spotted pardalote (Pardalotus punctatus) searching for insects in the leaf litter and dead branches. Photo: Geoff Park

We all want to protect our properties from bushfire. However, make sure you check the latest research and guidelines on fire hazard reduction. Some historical practices are now considered ineffective for fire control but highly damaging for the environment. For example, removing leaf litter creates bare ground which often encourages weed growth, creating its own fire hazard. If you do need to remove logs and branches for safety or access, consider moving them to another location where they can continue to provide habitat.

This factsheet is part of a larger project called ‘Regenerate before it’s too late‘ that engages the community about the importance of old trees and how to protect them. We are most grateful for the generous project support from the Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation . The foundation aims ‘To encourage and support organisations that are capable of responding to social and ecological opportunities and challenges.’ To learn more about Ian & Shirley Norman Foundation – click here

Revegetation in a changing climate captures audience

Posted on 4 September, 2023 by Ivan

On Tuesday 1 August 2023, over 60 people gathered at the Castlemaine Anglican Church Community Hall to hear excellent presentations from a variety of guest speakers addressing how we can plan revegetation in a changing climate for best success. The strong mid-week, mid-winter audience heard from Sasha Jellinek (University of Melbourne), Oli Moraes from DJAARA and Tess Grieves from the North Central Catchment Management Authority (NCCMA). The evening was completed with a Q&A panel session to answer the audience’s questions and give reason for hope in the future.

The overall learning and topics revolved around how we can use climate prediction modelling to consider future vegetation growth conditions and adapt current practices to future-proof our landscapes.

Lead guest speaker, Sasha Jellinek, covered where to find information on climate projections and future scenarios, as well as sourcing seeds from a mix of local and different bioregions, and how to make up this mix. Sasha is an experienced ecologist with a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) focused on Ecology from the University of Melbourne and has worked across many fields. He was involved in the production of Greening Australia’s ‘Establishing Victorias Ecological Infrastructure; A Guide to creating Climate Future Plots‘ which is a great resource for those embarking on this road.

Oli presented DJAARAs recently released Climate Change Strategy and talked about how we can approach revegetation projects using cultural knowledge and wisdom. Tess provided a great overview of the NCCMAs climate resistance projects and how they have been incorporating climate change modelling into their project planning and implementation.

A highlight of the presentations was the passion, dedication and knowledge of all three guest speakers, and we thank them for sharing so that we can all start planning for future success.

The event was recorded by the wonderful Ally from Saltgrass Podcasts and is available here.

This event was part of a larger project called Future Proof our Forests, where Connecting Country has established Climate Future Plots to monitor the success (or otherwise) of revegetation sourced from a variety of climates.

We would like to thank the Ross Trust for their generous funding for this important project. The Ross Trust is a perpetual charitable trust with a vision to create positive social and environmental change so Victorians can thrive.

Learn more:

For more information on climate future plots, see:

https://www.greeningaustralia.org.au/climate-future-plots/

https://connectingcountry.org.au/what-is-a-climate-future-plot/

Bird of the month: Nankeen Night-Heron

Posted on 21 August, 2023 by Ivan

Welcome to Bird of the Month, a partnership between Connecting Country and BirdLife Castlemaine District. Each month we’re taking a close look at one special local bird species. We’re excited to join forces to deliver you a different bird each month, seasonally adjusted, and welcome suggestions from the community. We are blessed to have the brilliant Jane Rusden and Damian Kelly from BirdLife Castlemaine District writing about our next bird of the month, accompanied by Damian’s stunning photos.

Nankeen Night-Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus)

After a frustrating afternoon trying and unfortunately failing to photograph Brown Falcons and Nankeen Kestrels on the Moolort Plains, Ash Vigus and I nearly gave up and went home. But at the last minute, just as we were losing light with encroaching dusk, we were thrilled to stumble on an immature Nankeen Night-Heron. Incredibly cryptic, they merge into the background and almost disappear, except in this case because it did a big spray of poop from its tree branch perch, which was very obvious when it hit the water below.

Immature Nankeen Night-Heron at Carin Curran Reservoir. Their plumage is quite different to the adult birds. Photo by Jane Rusden

A large poop has to come from a large bird, at 65cm in length and a wingspan of up to 1 metre, Nankeen Night-Herons are exactly that. Despite their size and the less camouflaged plumage of the adult birds, they remain masters of disguise, melting into foliage and becoming unnoticeable. They love roosting in dense vegetation and mostly forage at night to compound the difficulty of spotting them. When they vocalise, their loud croak or squawk is generally heard at night too. I always find it curious that the Herons, generally incredibly elegant birds, have the most hideous calls. However, they are calling to each other, not for the sake of our ears.

Herons are generally associated with water, the Nankeen Night-Heron is no exception, living, foraging and breeding along the margins of water. They inhabit the edges of lakes, rivers and coastal water bodies, good spots to hide and stealthy hunt for insects, crustaceans, frogs and fish. Their varied diet may also include house mice that wander too close to the Nankeen Night-Herons lethal stabbing bill, or even human refuse. You might be lucky to see one in the early morning, feeding along the edge of shallow water in local places like the Loddon River, Cairn Curran and the Castlemaine Botanical Gardens, they can also be found at Melbourne Botanical Gardens and Lake Wendouree in Ballarat.

Everything about the Nankeen Night-Heron is connected to water, including breeding, which can happen at any time of the year, always in response to rainfall. They congregate all over Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea in suitable habitats, to breed in large colonies, often alongside other species of water birds such as Ibises, Cormorants, other egrets and my favorite, Spoonbills. Their stick nests are loosely made and situated over water. In days gone by, before widespread habitat degradation like the draining of swamps, there have been recordings of up to 3000 birds spread over 21 hectares, all breeding. Nankeen Night-Herons will lay 2-3 eggs, which are incubated by both parents, both parents also feed the young hatchings.

Good luck looking for this secretive species, you’ll need plenty of patience and very sharp eyes to find them, move slowly and try not to startle the wary but beautiful Nankeen Night-Heron.

You can listen to the Nankeen Night-Heron call by using the audio button here.

Jane Rusden

Damian Kelly

2023 National Tree Day: Community planting a huge success!

Posted on 14 August, 2023 by Hadley Cole

To celebrate 2023 National Tree Day, Connecting Country teamed up with Mount Alexander Shire Council, Mount Alexander Youth Advisory Group and the Post Office Hill Action Group to host a community planting day on Sunday 30 July 2023.

Community members had the opportunity to take local on-ground conservation action to protect and enhance biodiversity by planting indigenous plant species across sites at Post Office Hill Reserve in Chewton.

A recent Council survey found that the younger generations of our community are seeking opportunities to plant trees, make homes for wildlife and to undertake practical actions to address climate change. In response to this call for action, the community planting idea was conceived and the younger generations of our community came along in hordes to connect with nature and plant trees for generations to come.

Over seventy community members of all ages attended the event and enjoyed a range of activities from planting to badge making, colouring and bird walks.

Young Post Office Hill Action group member and budding bird watcher Tavish, teamed up with Jane Rusden from Birdlife Castlemaine to guide a bird walk for aspiring bird watchers. Youth Advisory group members, Thea, Billy, Lucia and Tanisha, set up a badge-making station to create badges promoting woodland birds of our region. The friendly Post Office Hill Action Group members worked enthusiastically to guide participants in the best planting practices for the site. It truly was a team effort!

The Connecting Country team greatly appreciate all the many hands that made light work out of a busy morning. A special thank you to Post Office Hill Action Group for hosting the event and for their commitment to protecting and restoring the Post Office Hill Reserve over many years. We know the plants planted on the day are in good hands and will be nurtured over the coming months.

Attendees reported that they enjoyed a wonderful morning out in nature, as well as the free lunch provided by Mount Alexander Shire Council.

This event was made possible due to the generous contribution from community members who supported our ‘Trees for the next generation’ GiveNow campaign throughout June and July 2023. We know that our local community cares deeply about biodiversity conservation for future generations, but we were still blown away by the generous donations. A big THANK YOU to our generous members, supporters and the broader community who supported this event.

We look forward to doing it all over again in 2024! See you there.

Connecting Country staff welcome participants to Post Office Hill Reserve. Photo by Connecting Country.

Bird of the month: Painted Button-quail

Posted on 18 July, 2023 by Ivan

Welcome to Bird of the month, a partnership between Connecting Country and BirdLife Castlemaine District. Each month we’re taking a close look at one special local bird species. We’re excited to join forces to deliver you a different bird each month, seasonally adjusted, and welcome suggestions from the community. We are blessed to have the brilliant Jane Rusden and Damian Kelly from BirdLife Castlemaine District writing about our next bird of the month, accompanied by their stunning photos.

Painted Button-quail (Turnix varius)

It’s always exciting to find side plate-sized, circular patches of bare dirt in amongst leaf litter, because in the Castlemaine region it can only mean one thing … quiet, cryptic and difficult to see Painted Button-quail. Recently I found these bare patches in the bush by my front gate, hidden in leaf litter under shrubs. These “platelets” of cleared ground are formed whilst the bird is foraging, by standing on one foot and rotating in a tight circle as they scratch the ground with the other foot. In NSW and Qld Black-breasted Button-quail also make platelets, making both species of Button-quail rather unusual. So what are Painted Button-quails searching the ground for? Their delicious dinner of course, which comprises of insects and their larvae, seeds, small fruits, berries and vegetation. So their diet is pretty broad.

Dry open forest with sparse shrubs, and a ground cover of native grasses and dense leaf litter, in Muckleford Forest for example, is perfect habitat for Painted Button-quail. Being such a camouflaged species which tends to walk from cover to cover, historically it’s been difficult to accurately assess their numbers and distribution. However, using newly developed technology such as sound recording, motion-detecting and thermal camera, cryptic species such as the Painted Button-quail have become easier to monitor. Interestingly they have been found in a diverse range of habitats from dry ridges in moister forest, in coastal sand dunes and even forest edges where it abuts farmland. Curiously, Painted Button-quails will move into a newly burnt area after fire, but once the forest returns, they leave. This has been observed in the Otway Ranges and in Tasmania.

The female Painted Button-quail lays her eggs in a saucer-shaped hollow on the ground beneath some cover such as a tuft of grass, small bush or dry debris. She is Polyandrous and after laying 3-4 eggs and she moves on, makes her booming call day or night, advertising for another male to mate with and lay more eggs. She can do this 3 or 4 times in a breeding season. Dad is the stay-at-home parent, he incubates and feeds the young chicks.

We don’t have sand dunes in central Victoria, but I have seen Painted Button-quail on dry ridges and on the edge of forest in Campbells Creek and in the wider area of Castlemaine, Newstead and Guildford. Last spring I stopped the car quickly, as a Dad escorted his 3 tiny golf ball size fuzzy chicks walking across Rowley Park Road, it was the cutest thing you ever saw.

Painted Button-quail doing what it does best, hiding and camouflaging into leaf litter. Photo by Damian Kelly

To listen to the call of the Painted Button-quail – click here

Jane Rusden

Damian Kelly

Bird of the month: Diamond Firetail

Posted on 26 June, 2023 by Ivan

Welcome to Bird of the Month, a partnership between Connecting Country and BirdLife Castlemaine District. Each month we’re taking a close look at one special local bird species. We’re excited to join forces to deliver you a different bird each month, seasonally adjusted, and welcome suggestions from the community. We are blessed to have the brilliant Jane Rusden and Damian Kelly from BirdLife Castlemaine District writing about our next bird of the month, accompanied by Damian’s stunning photos.

Diamond Firetail (Stagonopleura guttata)

Connecting Country’s Feathered Five includes the small but striking Diamond Firetail. It is a tricky bird to find, but not impossible. Their conservation status was unfortunately recently upgraded to Vulnerable under the EPBC Act. It means that over the last 10 years, the population has an estimated decline in the region of 30-50%, with a high probability of declining further in the future. No wonder they are such a hard bird to see.

It’s all in the bright red bill … the shape indicates it’s a finch, and finches eat the seeds of native grasses. The decline of the Diamond Firetail is one result of native vegetation clearance and habitat degradation. Where perennial native grasses manage to persist (despite invasive annual exotic grasses taking over in many places), they struggle to produce the seed the Diamond Firetail needs at critical times of the year, largely because of overgrazing and invasive herbivores such as rabbits. Grazing animals also take out shrubby habitat which these little birds need for protection. This means our gorgeous Diamond Firetails may go hungry in late autumn and winter and are more vulnerable to predators, such as foxes and cats.

The healthy diet for the Dimond Firetail isn’t just native grass seed, they also require some insects, especially for the baby birds still in the nest who are growing rapidly.

Clutch size ranges quite widely, from 3-7 eggs. If conditions allow and food sources are plentiful, a pair of Diamond Firetails may have more than one clutch in a season. The nest is a beautifully constructed bottle shape with a tunnel entrance, or a ball shape with a small hole for an entrance, made from grass and twigs and lined with feathers. They are good little recyclers, because sometimes rubbish such as fishing line, frayed plastic and drinking straws are incorporated into nests. Both parents build the nest, sit on eggs to incubate the chicks, and then feed chicks when they hatch.

Damian recently took this beautiful photo of a Diamond Firetail at Rise and Shine Bushland Reserve. Photo by Damian Kelly.

A bit more on nests – the Diamond Firetail can make some interesting choices in nesting sites. They are a flock bird, getting around in small mobs of 5-30 birds. This extends to nesting, where they often nest in small groups, or colonies, with a number of nests in the same place. That place may be in the base of other much larger birds stick nests, such as White-faced Heron, Square-tailed Kite, Whistling Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Wedge-tailed Eagle, Brown Falcon and Kestrel nests. You’ll notice most of those birds are raptors, you’d think it a scary prospect, but White-browed Babblers think it’s a great idea too, and have been known to take over Diamond Firetail nests. Maybe it’s a deterrent to other predators?

Another way it’s thought Diamond Firetails avoid predators is the mechanics of how they drink. Like pigeons, they suck up water instead of dip and sip, then tilt the head back. The theory is it’s much quicker to slurp your water down in big gulps!

To listen to the call of the Diamond Firetail – click here

Jane Rusden

Damian Kelly

Friends, Supporters and Community: Donate a tree for our youth

Posted on 26 June, 2023 by Ivan

With the end of the financial year looming, we are asking our friends, supporters and community to donate a tree for our youth to plant at National Tree Day in July 2023.

We are partnering with local Landcare groups and Mount Alexander Shire Council to deliver a National Tree Day event on Sunday 30 July 2023. The day will be open to everyone to participate and will include planting indigenous plants for habitat and learning more about our local landscape.

The tree planting event is answering a call from the younger generations of our community who, in a recent Council survey, asked for more opportunities to plant trees, make homes for wildlife and to undertake practical actions to address climate change.

We are raising funds to purchase local native plants and host a Community Planting Day to support the Mount Alexander/ Leanganook community – young and wise – to help heal the land.

How you can help: sponsor a community planting day!

You can sponsor the day by donating funds to go towards the purchase of the plants, stakes and guards.

If you wish, you can attend the community planting day, get your hands dirty and plant the plants you have sponsored. However, if you can’t attend the event, your contribution will be guaranteed and the community will plant for you!

Let’s work together to protect and restore our local biodiversity and nurture the land for our future generations!

Donate today via our Give Now page – click here

Donating to our ‘Trees for our next generation’ campaign provides excellent value for your investment:

- All plants purchased using the funds raised during this campaign will be from local nurseries that specialise in indigenous plants to this region. This is vital to ensure plants are adapted to local conditions, support local wildlife whilst supporting local businesses.

- Experienced volunteers from Landcare will be supporting the planting, making this an effective and highly efficient project.

- Our 15-year track record of landscape restoration and monitoring demonstrates the importance and relevance of this project and the excellent outcomes for local wildlife and community education.

- Restoring degraded bushland, which was turned upside-down during the gold rush, is an important community engagement activity and allows people who deeply care about our landscape to take direct action.

- The project will allow donors who wish to be involved on the day to plant a local native plant on National Tree Day, as well as passionate volunteers and younger generations.

- This project will support young people to undertake practical actions to address climate change and biodiversity loss – a key issue that young people are acutely aware will profoundly affect their generation.

Any funds raised above our target will go directly towards purchasing plants for other Landcare groups in our region.

Donate today via our Give Now page – click here

Photo Credit: Leonie van Eyk

We have a secure payment system and all donations (>$2) to Connecting Country are tax deductible.

Can’t donate? Here are some other ways you can help

- Attend the community tree planting event, and volunteer to revegetate the sponsored plants

- Share our campaign with your friends and networks.

- Retain leaf litter, logs, and trees (especially mature trees) on your property, as these provide foraging and den resources for wildlife

- Consider doing revegetation or installing nestboxes on your property

- Contribute to restoring healthy forests by joining your local Landcare or Friends group. To find a group near you – click here

The background story: Degraded bushland

The Mount Alexander region of central Victoria has a long history of removing native vegetation for gold mining, agriculture, and timber and firewood harvesting, leading to many areas of degraded bushland, with little understory, or suitable habitat. In Australia, it can take hundreds of years for trees to form natural hollows. Due to the profound environmental change caused by European colonisation and the gold rush, many trees in our region are still young and have little understory or ground cover. Connecting Country has nearly two decades of experience in restoring these landscapes, and will oversee the event, to ensure the maximum benefit for our local wildlife and community.

Sponsor a community planting day: Seeking YOUR help for 2023 National Tree Day

Posted on 31 May, 2023 by Ivan

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, the next best time is now, and we need your help!

We are partnering with local Landcare groups and Mount Alexander Shire Council to deliver a National Tree Day event on Sunday 30 July 2023. The day will be open to everyone to participate and will include planting indigenous plants for habitat and learning more about our local landscape.

The tree planting event aims to empower the younger generations of our community to take direct action in healing the land and tackling climate change. This is what they have asked for. Mount Alexander Shire Council recently surveyed young people in our local area. Our young people reported they want opportunities to plant trees, make homes for wildlife and to undertake practical actions to address climate change.

How you can help: sponsor a community planting day!

We are raising funds to purchase local native plants and host a Community Planting Day on National Tree Day 2023, to support the Mount Alexander/ Leanganook community – young and wise – to help heal the land. Through this project, we aim to connect people of all ages with nature and restore degraded bushland.

The sponsored plants will be provided by local indigenous nurseries. You can sponsor the day by donating funds to go towards the purchase of the plants, stakes and guards. If you wish, you can attend the community planting day, get your hands dirty and plants the plants you have sponsored. However, if you can’t attend the event, your contribution will be guaranteed and the community will plant for you! Let’s work together to protect and restore our local biodiversity and nurture the land for our future generations! Donate today – click here

Degraded bushland

The Mount Alexander region of central Victoria has a long history of removing native vegetation for gold mining, agriculture, and timber and firewood harvesting, leading to many areas of degraded bushland, with little understory, or suitable habitat. In Australia, it can take hundreds of years for trees to form natural hollows. Due to the profound environmental change caused by European colonisation and the gold rush, many trees in our region are still young and have little understory or ground cover. Connecting Country has nearly two decades of experience in restoring these landscapes, and will oversee the event, to ensure the maximum benefit for our local wildlife and community.

Donate today via our Give Now page – click here

We are reaching out to our community for support to purchase a selection of local native trees, shrubs and groundcovers, to allow us to restore bushland and support our younger generations and local community. Donating to our ‘Trees for our next generation’ campaign provides excellent value for your investment:

- All plants purchased using the funds raised during this campaign will be from local nurseries that specialise in indigenous plants to this region. This is vital to ensure plants are adapted to local conditions, support local wildlife whilst supporting local businesses.

- Experienced volunteers from Landcare will be supporting the planting, making this an effective and highly efficient project.

- Our 15-year track record of landscape restoration and monitoring demonstrates the importance and relevance of this project and the excellent outcomes for local wildlife and community education.

- Restoring degraded bushland, which was turned upside-down during the gold rush, is an important community engagement activity and allows people who deeply care about our landscape to take direct action.

- The project will allow donors who wish to be involved on the day to plant a local native plant on National Tree Day, as well as passionate volunteers and younger generations.

- This project will support young people to undertake practical actions to address climate change and biodiversity loss – a key issue that young people are acutely aware will profoundly affect their generation.

Any funds raised above our target will go directly towards purchasing plants for other Landcare groups in our region.

Photo Credit: Leonie van Eyk

Donate today via our Give Now page – click here

We have a secure payment system and all donations (>$2) to Connecting Country are tax deductible.

Can’t donate? Here are some other ways you can help

- Attend the community tree planting event, and volunteer to revegetate the sponsored plants

- Share our campaign with your friends and networks.

- Retain leaf litter, logs, and trees (especially mature trees) on your property, as these provide foraging and den resources for wildlife

- Consider doing revegetation or installing nestboxes on your property

- Contribute to restoring healthy forests by joining your local Landcare or Friends group. To find a group near you – click here

Bird of the month: White-fronted Chat

Posted on 18 April, 2023 by Ivan

Welcome to Bird of the month, a partnership between Connecting Country and BirdLife Castlemaine District. Each month we’re taking a close look at one special local bird species. We’re excited to join forces to deliver you a different bird each month, seasonally adjusted, and welcome suggestions from the community. We are blessed to have the brilliant Jane Rusden and Damian Kelly from BirdLife Castlemaine District writing about our next bird of the month, accompanied by Damian’s stunning photos.

White-fronted Chat (Epthianura albifrons)

Despite being quite common in certain areas, I get excited when I see a White-fronted Chat because they are not so common in Mount Alexander Shire. A very striking bird, especially the male with it’s distinctive black and white colouring. The female is a bit more grey and brown, but still has the beautiful white chest and belly with the stunning black chest stripe.

The White-fronted Chat’s range extends across the southern parts of Australia, avoiding the driest areas, Tasmania and some of the larger islands in Bass Straight. Locally they can be found on the Moolort Plains, along the edges of wetlands such as Cairn Curran and Lignum Swamp. This kind of habitat is typical for them as it’s essentially open grassland around open damp and possibly saline patches of ground.

Foraging amongst seaweed on Port Fairy beeches is where Damian Kelly took a photo of this male White-fronted Chat.

So, what is it that makes White-fronted Chats attracted to open areas of habitat? That would be food of course! They wander around, but don’t hop, foraging for insects and occasionally seeds, on the ground and in low shrubs. If startled, they will fly a short distance to a prominent perch such as a branch or fence. I’ve usually seen them perched on fence wires.

White-fronted Chats usually stay in one place all year round, however weather and food availability will encourage them to move when necessary. Banding recoveries have been from less than 10km from the original site where the bird was banded, indicating they don’t move far.

Female White-fronted Chat, with her grey head, on a fence wire, a very typical perch for this species.

Interestingly, behavioural studies at Laverton Saltworks in southern Victoria, revealed that White-fronted Chats are quite an adaptable species. Often they will be in flocks of 30 or so birds, with pairs often foraging together, they also communally roost when not breeding. Cooperative breeding (where non-parent birds help raise chicks), is not apparent in this species and breeding pairs may change over the years. However, they nest semi-colonially, with several nests close together. Essentially there will be a whole lot of breeding pairs, who are a bit fluid about who they are paired to, hanging out together most of the time, but doing their own thing.

The adaptability of the White-fronted Chat is highlighted in their breeding, being opportunistic in drier country, largely in response to rain and food availability. However, in wetter coastal areas breeding is seasonal. The nest is cup-shaped and usually, three eggs are laid. Both parents will brood and feed the chicks, and hopefully, a Horsefield’s Bronze Cuckoo won’t find them, to parasitize the nest with their egg.

To listen to the call of the White-fronted Chat – click here

Jane Rusden

Damian Kelly

Bird of the month: Silvereye

Posted on 27 March, 2023 by Ivan

Welcome to Bird of the month, a partnership between Connecting Country and BirdLife Castlemaine District. Each month we’re taking a close look at one special local bird species. We’re excited to join forces to deliver you a different bird each month, seasonally adjusted, and welcome suggestions from the community. We are blessed to have the brilliant Jane Rusden and Damian Kelly from BirdLife Castlemaine District writing about our next bird of the month, accompanied by Damian’s stunning photos.

Silvereye (Zosterops lateralis)

A moderately common sight year-round, in gardens with a suitable food plant or water source, are small flocks of tiny Silvereyes, also known as White-eyes. They are a delight to watch. At only 10-12 grams and 125 mm long, this tiny olive bird, with a pale chest and distinctive white or silver eye ring, is a miniature favourite.

Even their soft-sounding “Zcheee” contact call, is endearing, which is lucky because they are chatty and constantly calling to each other. Like so many Australian birds, they are also mimics and adept at copying other bird calls.

It’s amazing to ponder the distances these tiny birds can cover, banding studies have recorded movements from Margret River WA to Braidwood NSW, that’s 3,159 km of flying. Many birds including some in the Castlemaine area where they overwinter, fly 1,500 km between Tasmania and NSW, which means crossing the treacherous Bass Strait. Silvereyes being so mobile, their ranges cover Southern WA, all along the south coast of Australia and up the eastern coast, extending inland over the Great Dividing Range to the edge of central deserts.

The Silvereye is not only highly mobile, but highly adaptable as well. They eat a varied diet including nectar, fruits, insects and foraging in small groups. Enjoying soft fruits in your garden, sipping nectar from flowers including gums, and gleaning insects, moving from ground level and right up through shrub layers into the tree tops.

Although Silvereyes are usually in small flocks, during the spring breeding season they split into life pairs and defend breeding territories. Both parents brood the 2-4 eggs laid in a cup-shaped nest, once hatched both parents feed the chicks. Often Silvereye pairs attempt to rear two broods in a breeding season.

So keep an eye out for this diminutive bird in your garden and around town, with its distinctive silver eye ring and ability to fly such huge distances. That’s a lot of birds in a tiny fluff ball.

Silvereye in a fruit tree, with its buff coloured flank, indicating it’s the Tasmanian type bird, which can be seen overwintering in the Castlemaine area. Photo by Damian Kelly.

To listen to the call of the Silvereye – click here

Jane Rusden

Damian Kelly